If you still pay to go see animals perform at SeaWorld, please read this.

Dear Reader,

Orcas have held a special place in my heart since I was a child. At just three years old, I’d fall asleep with my nose buried in a marine biology textbook, dreaming of the majestic killer whales on its pages. These animals are more than iconic—they are deeply complex beings with tight-knit families, profound intelligence, and matriarchs who guide generations. Their unique ability to pass down wisdom reminded me, even as a child, of the extraordinary depth of their lives.

When asked what animal I’d be in various (yet multiple) job interviews, I’ve always said, “an orca.” A little bold, a lot fierce, but ultimately loyal, sensitive, and driven by love for my family. Growing up in the 90s, it shouldn’t be a surprise that Free Willy played on repeat in our house, its story igniting a passion in me that has never dimmed. Like many, I cheered for Willy’s freedom, but what stayed with me was the very real captivity endured by Keiko, the orca who brought Willy to life on screen.

I didn’t grow up to be a marine biologist like I dreamed, but my love for orcas endured. Years later, when Blackfish was released, exposing the heartbreaking realities of Tilikum’s life in captivity, my passion reignited. I followed Tilikum’s story closely, and when I learned of his painful death from a bacterial infection, I got my first tattoo—a simple ocean wave with the words “Swim Free” beneath it, nestled right on my forearm. It’s a small tribute to his stolen life and a hope that, wherever he is now, he knows the freedom he was denied.

A few years after Tilikum’s story was brought to life, I wound up at World Animal Protection US as a Wildlife Campaign Manager, where I worked to end the exploitation of marine mammals. One of my first campaigns targeted travel companies like Expedia, urging the company to stop promoting marine parks (which it eventually did) to reduce important revenue streams and promotional channels for venues like SeaWorld.

I read countless books on the subject: Death at SeaWorld and Beneath the Surface being so captivating I’ve re-read them countless times since. I wanted to know more about these amazing animals and their plight in captivity, and it’s as if my brain could not absorb the information quickly enough. It kept craving more.

But to fully understand the system I was fighting, I knew I had to see it with my own eyes.

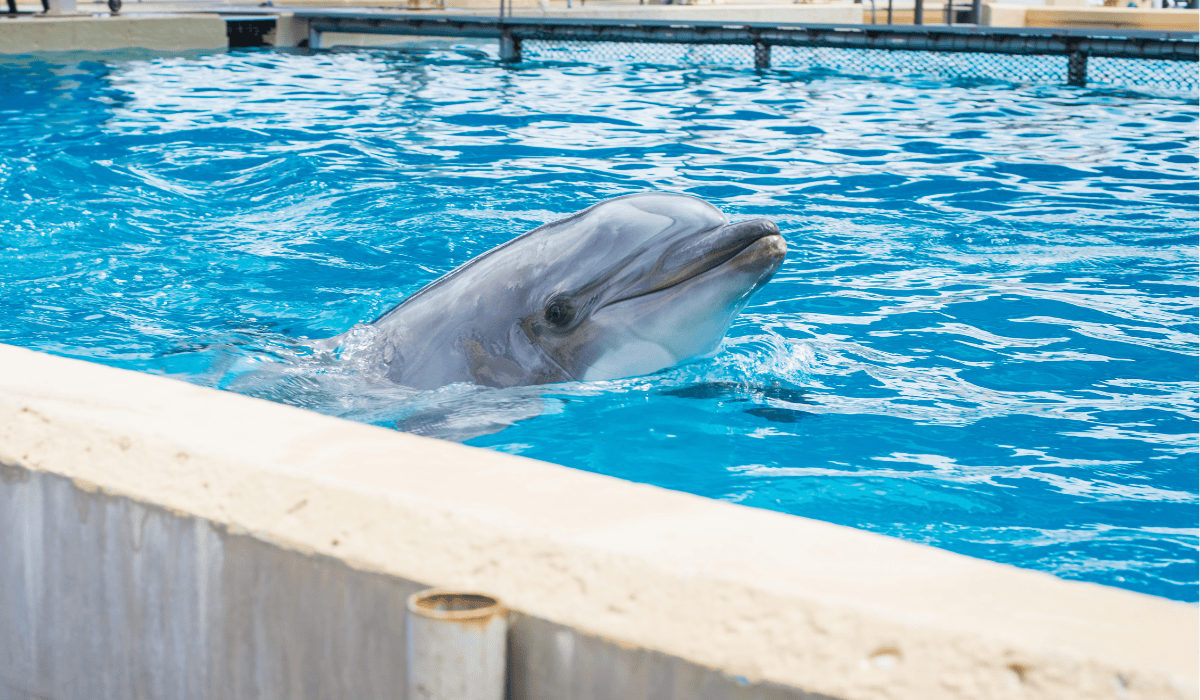

At SeaWorld Orlando, I watched orcas perform under the guise of “education,” despite the business’s press statements that killer whale performances would be ended. I saw dolphins swimming in endless, anxious circles in shallow pools, their jaws popping in aggression because they couldn’t escape the sharp teeth of their tank mates.

Behind the scenes, I saw the cramped pools where these massive animals are confined, deprived of the vast ocean they instinctively know as home. Roller coasters roared near the dolphin nursery and stadium, their vibrations likely drowning out the sensitive echolocation these animals rely on to communicate. It was a heartbreaking spectacle of misery dressed up as family entertainment.

A few months later, I visited SeaWorld San Antonio to gather information for a report we were releasing and saw the same horrors. I watched beluga whales forced to beach themselves so children could sit on them, orcas reduced to performing stunts, and dolphins coerced into unnatural dance moves, like breakdancing, for applause.

The tour guides and their playbooks were easy for me to see through. They weren’t experts on marine mammals. I was. They were mostly just young adults working a summer job, reciting a script someone gave to them. The trainers who performed with the animals were merely towing the company line.

I knew the names and backstories of the orcas performing. Some were mothers who’d had their calves ripped from their sides and shipped away to other parks. Others were the calves torn away.

Takara, for example, was one of the orcas trapped at SeaWorld San Antonio when I visited. Just a few months younger than me, Takara was torn away from her mother and transferred to SeaWorld Orlando at twelve years old, leaving her and her mother in visible emotional distress. She then experienced the same heartbreak as a mother herself, being transferred to SeaWorld San Antonio and leaving her son behind in Florida.

I saw Takara forced to perform after she endured such cruelty and heartbreak at the hands of SeaWorld executives. I knew her story and watched as she did flips and splashed the audience. If only the rest of the audience knew the story of her life, too.

Each time, I left the theme park in tears. My heart shattered. But here’s the difference: I got to leave. Those animals didn’t.

The suffering I witnessed wasn’t unique to SeaWorld. It’s the reality for every marine animal in captivity. These intelligent, sentient beings are denied everything that makes life worth living for them.

The orcas I so loved, the species I was so fiercely interested in, were stripped of everything that makes them who they are. Captivity has created animals who are shells of their counterparts living in the wild. “Ambassadors,” they’re called by zoos and aquariums, to hide what they really are: captives.

You have a choice. You can choose to enable their suffering or to stop it. By buying a ticket, you are helping to line the pockets of people who keep these animals in captivity despite knowing the immense suffering it brings them.

By not buying a ticket, and instead going to an animal-free venue or viewing these majestic animals ethically at a Wildlife Heritage Area, you’re refusing to participate in the cruelty that is marine animal theme parks. I urge you to consider the latter, and if you truly love animals, to support an end to their confinement.

Thank you for listening. And I hope you make the right choice.